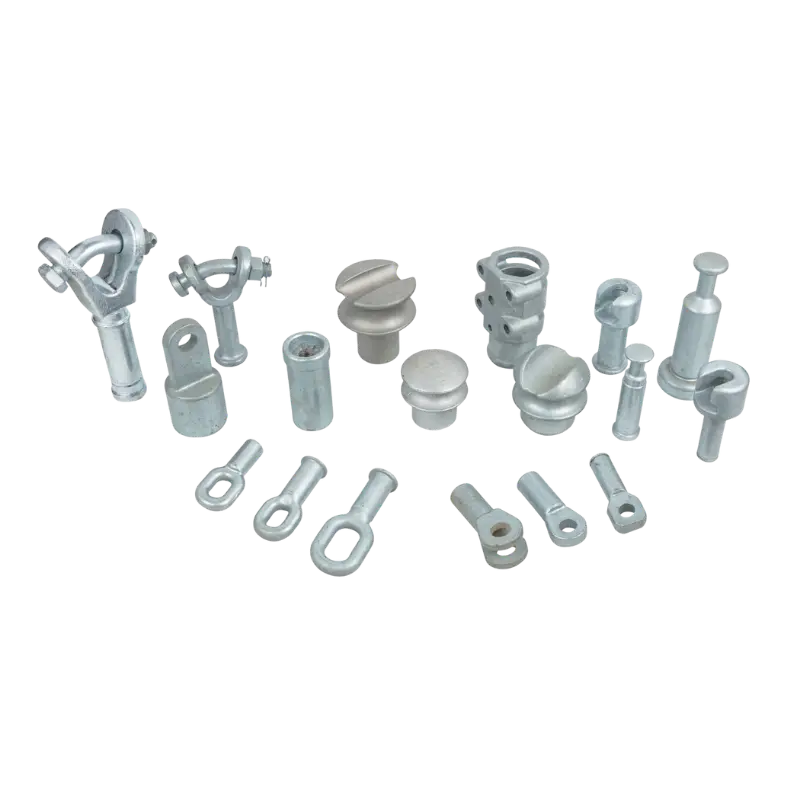

Forging is often chosen for strength and durability, but a forged part is only as good as the process control behind it. Forging defects can turn a “strong” component into a scrap part, or worse—something that passes visual checks but fails later during machining, pressure testing, or in-service fatigue. The frustrating part is that many defects don’t announce themselves early. They show up when you start cutting the part, when you inspect critical surfaces, or after heat treatment.

This article breaks down the most common forging defects, what typically causes them, how they show up downstream, and what you can do early to reduce risk—especially if your finished part relies on tight tolerances and CNC-machined interfaces.

What Are Forging Defects?

Forging defects are imperfections introduced during forming, trimming, cooling, heat treatment, or handling that reduce dimensional accuracy, surface integrity, or internal soundness. Some defects are mostly cosmetic, but many are structural—meaning they affect fatigue life, impact resistance, leak-tightness, or machinability. Because forging is a high-force process, defects often come from a small mismatch between temperature, material flow, die condition, lubrication, and deformation rate.

A useful way to think about it is: forging defects usually mean the metal didn’t flow the way the die designer expected.

Why Forging Defects Matter for Machining and Tolerances

If your component will be CNC-machined—threads, sealing faces, bearing seats, precision bores—then forging defects are not just a forging problem. They become a machining cost problem. Surface laps can open up into cracks when you machine down to final size. Scale pits can create pitting and poor surface finish on sealing areas. Internal cracks can remain hidden until machining exposes them, at which point you’ve already paid for forging, heat treatment, and multiple machining operations.

So when people discuss “forging vs machining,” the real goal is simple: get a sound forging blank so machining becomes predictable, not a rescue operation.

Common Forging Defects and What They Usually Mean

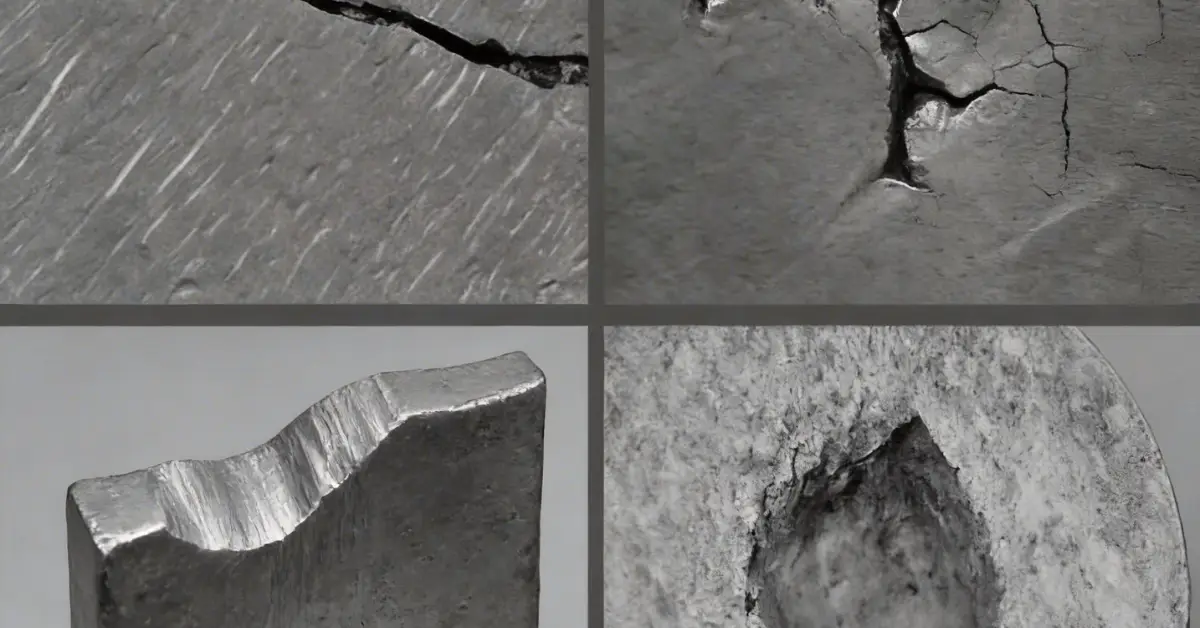

Laps, Folds, and Cold Shuts

These are among the most common and most misunderstood forging defects. A lap or fold is essentially a surface overlap where the metal folds onto itself instead of flowing smoothly. A cold shut is similar in appearance—two metal fronts meet but don’t fuse properly. These defects can look like thin lines or seams on the surface, and they’re dangerous because they behave like crack starters under cyclic loads. They’re often linked to die design, sharp transitions, poor preform design, incorrect stock size, or metal being too cold to flow properly into detail features.

Cracks (Hot Cracks, Cold Cracks, and Heat-Treat Cracks)

Cracks can happen during forging (especially if deformation is too aggressive or the material temperature window isn’t respected), during cooling (if thermal gradients are severe), or after heat treatment (if residual stresses are high or quench severity is too aggressive for geometry). Cracks are especially critical in high-stress parts because they can propagate under fatigue. Sometimes they are visible; sometimes they only show up after machining removes the surface layer.

Underfill and Unfilled Sections

Underfill means the metal did not fully fill the die cavity. You may see missing corners, shallow features, incomplete fillets, or weak edges. Underfill often points to insufficient billet volume, low forging temperature, inadequate press energy, poor venting, or a flow path that is too restrictive for the part geometry.

Die Shift (Mismatch)

Mismatch happens when the upper and lower dies are not aligned perfectly, producing a step at the parting line. It may look like a simple cosmetic offset, but it can reduce machining allowance on one side, shift datums, and create tolerance headaches. Mismatch is usually tied to die alignment, wear, setup control, or inconsistent press behavior.

Scale Pits and Surface Pitting

If التشكيل الساخن is involved, scale is part of the reality. Scale pits occur when oxide scale gets pressed into the surface or when scale breaks off and leaves pits. This matters for surface finish and sealing faces, and it can create extra grinding and machining stock. It’s often influenced by temperature control, atmosphere exposure time, and surface preparation.

Internal Bursts and Centerline Cracking

Some defects occur inside the forging due to stress states during deformation, especially in heavy reductions or poor process sequencing. These are the defects you don’t want to discover after you’ve machined the part. When they happen, it often points to deformation ratio, billet quality, forging sequence, temperature gradients, and reduction strategy.

Decarburization and Surface Layer Issues

Decarburization is the loss of carbon from the surface of steel when exposed to heat in oxidizing environments. It can reduce surface hardness and wear resistance, which is a problem for functional surfaces. Even when the forging is structurally sound, surface chemistry changes can affect performance and how the part machines or heat treats.

Quick “Defect to Downstream Symptom” Map

| Forging defect | What you’ll notice later | Why it becomes costly |

| Laps / folds / cold shuts | seam opens during machining, fails fatigue | acts like a crack starter |

| الشقوق | scrap after machining/HT, failed NDT | structural risk |

| Underfill | missing stock, weak edges, rework | cannot meet geometry reliably |

| Die shift (mismatch) | uneven machining allowance, datum drift | tolerance instability |

| Scale pits | pitted finish, sealing issues | extra grinding/machining |

| Internal bursts | hidden until machining/NDT | late-stage scrap |

Forging Defects Causes: What Usually Goes Wrong

Most forging defects causes fall into the same handful of patterns. Temperature is a big one—too cold and the metal won’t flow correctly; too hot and you invite grain growth, scaling, and surface problems. Die design and preform design matter because metal flow is not “automatic”; it follows the easiest path, and sharp transitions or poor volume distribution create folds, laps, and underfill. Lubrication and friction control influence how the metal fills and whether it tears or folds at the surface. Press energy, stroke profile, and forging sequence affect internal stress states and can drive internal cracking if the deformation path is wrong. Finally, post-forging handling—cooling rate, straightening, heat treatment—can either stabilize the part or trigger cracks if residual stresses are high.

When defects repeat across batches, it’s almost never random. It’s usually one variable drifting, or one design/process assumption that isn’t true for that geometry.

How to Reduce Forging Defects Before They Reach CNC Machining

The best strategy is to treat defect prevention as part of the “blank planning” stage, not as an inspection stage. That means aligning the part’s critical features with the forging method early, ensuring the preform and die design encourage smooth flow, and confirming that temperature windows and deformation ratios are suitable for the alloy and geometry. It also means being realistic about what will be forged-to-shape versus what will be CNC-finished, because machining allowances and datum strategy affect how sensitive the part is to mismatch and surface defects.

From a practical sourcing standpoint, you want the supplier to prove stability early through first-article validation and consistent process parameters, rather than relying on sorting and rework.

Forging Inspection Methods That Catch Problems Early

Visual inspection is useful, but it won’t reliably catch internal defects or fine surface seams. For critical parts, it’s common to use inspection approaches that can detect surface-breaking cracks and internal discontinuities, and to verify that the forging is consistent before high-value machining steps begin. The specific method depends on material, geometry, and requirement level, but the key idea is the same: detect defects before you pay for CNC time.

FAQ: Forging Defects

What are the most common forging defects?

The most common forging defects include laps/folds, cracks, underfill, die shift (mismatch), scale pits, and internal cracking that may only be detected by inspection or after machining.

What causes laps and folds in forging?

Laps and folds often come from improper metal flow, which can be driven by die geometry, sharp transitions, incorrect billet size, poor preform design, low forging temperature, or friction/lubrication issues.

How do forging defects affect CNC machining?

Forging defects can expose voids or seams during machining, ruin surface finish, reduce tool life, and create late-stage scrap when defects appear after you’ve already added machining value.

Can forging cracks appear after heat treatment?

Yes. Cracks can form or grow after heat treatment if residual stresses are high, quenching is too severe for the geometry, or if a small defect existed and becomes critical during thermal cycling.

What is die shift (mismatch) in forging?

Die shift is misalignment between the upper and lower dies, creating an offset at the parting line. It can reduce machining allowance on one side and cause datum and tolerance instability.

Are scale pits a serious defect or just cosmetic?

They can be cosmetic, but they become serious when the surface is functional—like sealing faces, bearing seats, or fatigue-sensitive areas—because pits can drive leaks, poor finish, or crack initiation.

How can I reduce the risk of forging defects on a new part?

Reduce risk by aligning forging method and geometry early, ensuring proper machining allowance and datum strategy, validating first articles, and using inspection before high-value machining steps.

خاتمة

Forging defects are often the hidden driver behind scrap, rework, and unpredictable machining time. When the forging is sound and stable, CNC machining becomes straightforward: consistent stock, predictable tool life, reliable datums, and fewer surprises at inspection. When defects slip through, machining becomes damage control.

If your part is tolerance-sensitive or performance-critical, the best outcome usually comes from addressing defect prevention early—through process control, proper blank design, and inspection before machining—so you’re not paying CNC time to discover problems that started upstream.

At HDC Manufacturing, our تشكيل القوالب عن قرب process is supported by metal flow simulation to analyze how material fills the die and where defect risks may occur—helping improve forging stability before CNC machining.